Graduation attire is not just for show—it tells a story

Academic regalia reaches far back into the early days of the oldest—and coldest—universities.

During the Middle Ages, scholars at the earliest English and European universities wore wool or fur garments to stay warm in the drafty, stone buildings. Many of these early scholars were also members of the clergy, often distinguished by the shave crown of their heads (the clerical tonsure) and cloaks with hoods that served both practical and symbolic purposes.

The academic gown made its first recorded appearance at the University of Cambridge in 1284. The tradition crossed the Atlantic Ocean with King’s College in New York—now known as Columbia University—and took root in the United States.

By the late 1800s, representatives from American universities came together to standardize academic dress, creating the Intercollegiate Code for Academic Costumes. This system gave meaning to the colors and designs of the caps, gowns and hoods, allowing observers to “read” a graduate’s academic journey—from their degree level to their alma mater—simply by looking at their regalia.

Today, while the hoods and robes may no longer be needed for insulation, they continue to signify years of hard work and academic achievement. The hood, specifically, remains reserved for those who have earned advanced degrees beyond the bachelor’s level—a mark of the highest academic honor.

The colors

The colors used on gown trim, hood edging and cap tassels represent specific academic disciplines and professional fields. Here are a few examples:

Arts and Humanities – white

Education – light blue

Philosophy – dark blue

Science – golden yellow

Medicine – dark green

Dentistry – lilac

Business – drab/brown

Nursing – apricot

Law – purple

Occupational therapy – ink blue

Pharmacy – olive green

Physical Therapy – teal

The gown

Black is the traditional color for academic gowns. The sleeve style changes depending on the degree: bachelor’s gowns have long, pointed sleeves; master’s gowns feature oblong sleeves with slits at the ends; and doctoral gowns stand out with full, bell-shaped sleeves, velvet trim on the front and neck, and three velvet bars on each sleeve.

The cap

In the U.S., the most common graduation cap is the square, tasseled mortarboard. Master’s and doctoral graduates, as well as faculty, often wear the "soft cap" or tam—a round velvet hat with a more classic style. During the ceremony, graduates start with the tassel on the right side of their cap and move it to the left after receiving their degree to mark their new academic achievement.

The hood

The hood is one of the most recognizable parts of academic regalia, showing both the wearer’s degree and the institution where it was earned. The inside lining of the hood features the school’s colors—white and blue for Creighton graduates—while the velvet trim represents the degree earned. At Creighton, bachelor’s degree candidates do not wear hoods, while master’s and doctoral candidates have theirs placed upon them during their ceremonies.

Seniors reflect on their stoles

Graduation stoles and sashes are symbols of club involvement, academic achievements—and even life-changing experiences for a few Creighton seniors.

Mason Dasig, an exercise science major and biology minor, plans to wear the white and light green stole with flower leis representing Hui ‘O Hawai’i (Creighton’s Hawaii Club). “The club provided me with a home away from home,” says Mason, who is from Pearl City and was the operations executive chair of the club’s annual Lū’au.

“It means a lot to me because not only was this club a huge part of my growth as an undergraduate student, but it also represents my roots and my upbringing,” says Dasig, who will be attending Creighton’s Physician Assistant Program this fall. “Hawaii has taught me so many things and I wouldn’t be in the position I’m in now without my home.”

Stephanie Hernandez, a sociology major and political science minor from Omaha, will wear two stoles from the Creighton University Latino Student Association, where she served as secretary and public relations chair.

“It represents my culture as well as the breaking of barriers and generational cycles,” says Hernandez, a Grit Scholar. “I’m proud to be part of this moment and excited to see what comes next—for both me and others.” After graduation, she plans to study for the LSAT and pursue a future in immigration law and advocacy.

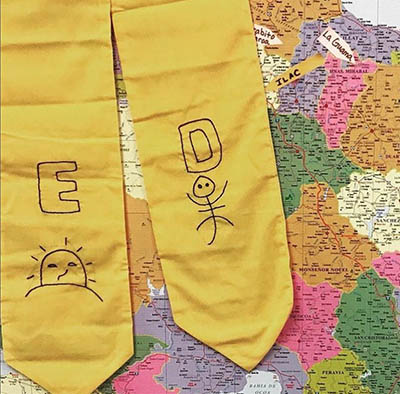

For the graduating seniors who participated in Creighton-ILAC’s Encuentro Dominicano program in the Dominican Republic, they will don bright yellow graduation stoles, which were handmade by women in the campos, the rural communities in close partnership with the ILAC programs.

For Abby Braden, wearing the stole “means everything to me.” Braden, an environmental science major and Spanish and public health minors, participated in Encuentro Dominicano during her fall semester of sophomore year.

“The stole being handmade mirrors the care, attention and genuine hospitality I received from everyone I encountered,” says Braden, who plans to volunteer with the Peace Corps in Peru before pursuing a graduate program in public health.

“I’m so grateful, not just for the stole, but for getting to represent experience behind it. It’s a tangible reminder I can hold onto and is one that reflects the strong bonds we built with each other and the community in such a short time.”

McKenna Blaine’s first ILAC experience began after her freshman year, when she participated in the Summer Health Program. “From that first experience,” she says, “I was deeply impacted and felt called to return.” The following summer, the studio art major returned to the Dominican Republic to participate in the Water Quality Program, then again in the fall of her junior year for Encuentro.

“I’ve lived in campos with host families and my host moms were some of the most generous and loving people I’ve ever met,” says Blaine, who will do a year of service with the Jesuit Volunteer Corps in Portland, Oregon, before applying to dental school.

“The stole reflects the heart of what my time in the DR meant to me—being welcomed into a community with open arms and a new family. For me, the stole is more than a gift, it’s a symbol of the relationships I built, the lessons I learned, the connections made and the sense of shared humanity.”