NIH grants Coffin $1.3 million grant to study medicine-induced hearing loss

How does an intended marine biologist who wanted to chase sharks end up as a biomedical researcher in a landlocked state studying zebrafish? Hearing loss research, of course.

Let’s fill in the (obvious) blanks.

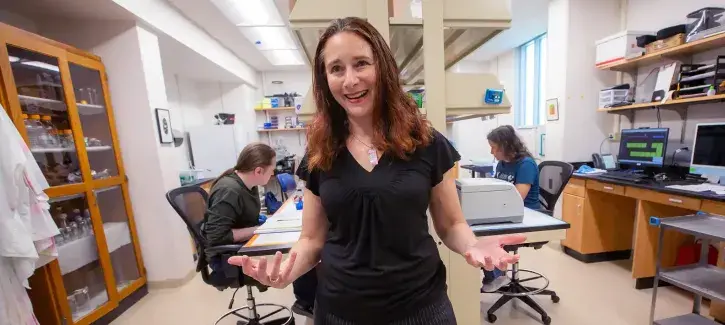

Allison Coffin, PhD, associate professor of Biomedical Sciences and president of the Association of Science Communicators, originally pursued a career as a marine biologist specializing in sharks. But when she learned that some fish could produce sound and had ears, the discovery so intrigued her that she made it the focus of her doctoral research at the University of Maryland. Then, her mentors introduced her to the parallels between fish and human hearing, an insight that redirected her post-doctoral work at the University of Washington. She began specializing in hearing loss caused by certain pharmaceutical therapies, carving out a path as a biomedical researcher.

To continue her work, the NIH awarded Coffin a $1,308,665 R01 grant to study the effects of medications on hearing. When she joined the faculty six months ago, the grant followed her to Creighton University and its Dr. Richard J. Bellucci Translational Hearing Center. The center, a collaboration between Creighton’s School of Medicine, Boy’s Town National Research Hospital and the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC), seeks to preserve and restore hearing and vestibular function through cutting-edge research.

Recent healthcare crises have provided rare opportunities to accelerate research into hearing loss as a potential pharmaceutical side effect—reserach which, up until this time, had been limited. Research teams around the world were conducting hundreds of clinical trials in individuals who had contracted certain illnesses, testing anti-inflammatory and anti-viral drugs against the viruses. Coffin’s research on the possible relationship between certain pharmaceutical treatment plans and mild hearing loss could piggyback on the clinical trials, benefiting from a massive data set that was now at her disposal.

It was a convergence of opportunity that allowed Coffin an incredible chance to learn more about what causes hearing loss. “Ultimately, it’s all about developing safer medications,” Coffin says.

Now, back to the zebrafish. Or, as Coffin calls them, “swimming eye lashes,” because in their larval state, that’s what they resemble.

Zebrafish have hearing cells on the outside of their bodies. They are also prolific breeders, producing hundreds of eggs per week. Coffin and her team test for potential medicine-induced hearing loss by having zebrafish swim through different drugs and then examining the fish’s hearing cells (they glow green) under a microscope. If any medication induces a 20% loss of cells, it advances to the next stage—testing in mammals, such as rats and mice. And if the medication once again reaches or exceeds the 20% threshold, then, says Coffin, “we start talking to clinicians about their patients who are receiving these medications.”

Coffin is still building her team, which currently includes two lead technicians, two Creighton graduate students and two Creighton undergraduates. She will be hiring a post-doc soon. The team can test approximately 20 drugs a week; thus far, they have analyzed 300 and hope to assess 500 total.

As a scientist, Coffin says the NIH grant helps her advance the field of study, which ultimately results in safer medications for future patients. She loves the fact that the work she and her team (and the zebrafish) do today will give individuals confidence in the treatment plans their doctors prescribe. Given the hefty price tag of running labs in which ground-breaking research takes place, the grant also means that scientific advancement can continue—and continue at Creighton, she adds.

Grants such as those the NIH awards not only create a new and/or improved body of knowledge, Coffin continues, but they generate economic health for the local community. They create jobs and serve as invaluable recruitment tools.

Within the last 18 months, Creighton has recruited five new biomedical faculty members who are also noted scientists.

We like the sound of that.